I’m just testing the Jetpack (A WordPress plug in) feature which allows you to send a blog post by e-mail.

The South Sea MOOC

A colleague has drawn my attention to this excellent post over at Posthegemony. The author argues, quite reasonably that a lot of the on line learning models draw from the sciences and are thus unsuitable for use in the humanities.

Now, I’d be the first to accept that I’m a bit of a sceptic with regard to technology. I use it alot, and I couldn’t really imagine life without Google, (even if they are telling the CIA what I’m up to every day) or the myriad of apps I use (I’m rather taken with the neat “to do” list app from Todoist.com at the moment, and I love playing with Mapmyride) but I don’t see tech as a panacea. I’d go further than Posthegemony though. I’m not sure that the multiple choice assessment model is all that helpful in the sciences either, at least not in terms of increasing understanding. I’ve been taking part in a MOOC (Well, in a pilot of one), and one of the tasks was to evaluate another course. I chose the Khan Academy Maths course.

While I do quite like the presentation style of the Khan videos I’ve seen, the tests it provides seem to do little more than test arithmetical accuracy. Of course accuracy is important in science but it’s no use without understanding the underlying conceptual structure and there’s no way (that I can see) of acknowledging that a student has understood a concept, or even partially understood it. The real skill in teaching, in my view is getting students from that state of partial understanding to complete understanding (and yes, “bigging up” the students own role in that journey.)

I think computers are long way from that yet, and what we’re seeing is a “bubble” along the lines of the South Sea Bubble, or Tulip Fever of centuries past. I do not doubt that when someone develops software that can display the sort of empathy that a human teacher has, that is the ability to analyse what is wrong and why, as opposed to merely seeing that something IS wrong, we will indeed see considerable profits from on-line education. But I don’t think we’re anywhere near that yet.

Digital learning and Elizabethan Poetry

In recent weeks I’ve been involved in the pilot of an online course delivered via the University’s VLE. The course is called “Teaching and Learning in the Digital Age” and it’s time for our first output. We’re to upload a poster outlining the advantages and disadvantages of digital learning. But I sometimes like to think outside the box. So here’s one I thought of that I’m NOT going to submit for assessment.

You may wonder what that has to do with the exercise. Well, in my view, Donne, writing long before anyone had ever heard of a computer nailed a fundamental problem of digital learning. He was (as poets are wont to do) talking about love, and its associated joys and pains, and how by versifying he could simplify and “fetter” those emotions.

If we substitute “knowledge” for “love” it strikes me that there’s a parallel. It is possible to reduce knowledge to “numbers”, to fetter it in some kind of digital chain. That can be convenient, certainly, sometimes it might even be necessary, but the act of doing so means that it loses something essential to itself and, as Donne found to his annoyance it needs to be, and inevitably will be, set free again if it is to “delight many”, if “whole joys” are to be experienced. (That last phrase is pinched from another Donne poem, wholly unsuitable for a respectable blog like this). So my poster can be summarised thus:-

- The advantage of digital learning is that it can render knowledge into a convenient package.

- The disadvantage of digital learning is that knowledge does not fit into a convenient package.

I plead guilty to exactly the kind of oversimplification that I’m criticising. I know that there is much more to digital learning than just “packaging knowledge”, but I don’t think it is really possible to talk about “digital learning”, or any sort of learning outside the context of the disciplines and without some sort of commitment to a critical pedagogy. The sort of knowledge we deal with in universities doesn’t lend itself to being reduced to numbers, or for that matter to lists of advantages and disadvantages. Instead it invites questions of itself about what it is for, and about the dialectic between the knower, the knowledge, and the discipline. Or it should.

Anyway I like the rhythm of the poem, and if this post gets one more person enjoying Donne I’ll think writing it an hour well spent. And yes, he’s just as entertaining online as he is in print.

The practice of writing

Writing is a habit I have let myself neglect since completing my doctorate, and that is a very bad thing. One of the things I am always telling my students is no matter how short of ideas you are, sitting down and writing is a brilliant way of organising your thinking. My own preference is (well, all right, was) to try and force myself to sit down and write for an hour (0utside my normal work activities) at least 5 days a week. I also believe that you should always keep at least one day a week free of any work, and I think it’s a good idea to keep one evening a week free too. I suppose that makes me a sabbatarian. Good Heavens! That had never crossed my mind before which just goes to show that writing can help you think about yourself in new ways.

A policy of writing regularly though, does raise some questions. One, of course is what should you write about. For anyone working in an academic department, that shouldn’t present too many problems. There are lots of research questions, and given the “publish or perish” atmosphere of many universities most academics spend their evenings beavering away on some worthy treatise or other anyway.

Blogging, as with my post about attendance monitoring yesterday serves a dual function, of disciplining your thoughts and, of publicising what you’re doing, which might help you network with colleagues working in similar areas. Another question is that of where you should write. I don’t mean physical location here, but rather should you blog, write word documents, use a tool like Evernote, or just scrawl in an old exercise book. I suppose you could even spend your writing hour contributing something to Wikipedia. All options have merit, but I do think there’s something to be said for publicly sharing your writing. If nothing else, there’s a potential for a kind of putative peer review, although I think you have to accept that most of your blog posts will never be read. (Come on now, how often do you read your old posts?). That said, it is quite nice to be able to have all your ramblings accessible in one place, so when you do come across an idea or a concept that you remember having talked about before you can at least see what you thought about it last year. And if you really don’t want to write in public there’s always the option of a private post.

The final point I want to make here – and this is really a post to myself, is that writing is hard work. It’s physically demanding, and that shouldn’t be underestimated. I can feel my eyelids beginning to stick together, even as I write and there’s a much more subtle demand it places on the body – that of underactivity. Once the flow does start it’s tempting to sit and bang on for hours. That’s not a good thing, either for ones health, or for one’s readers. So I’ll shut up now.

Should Universities monitor the attendance of their students?

(Photo credit Mikecogh - http://www.flickr.com/photos/mikecogh/4059881871/sizes/m/ CC-BY-NC-SA)

I’ve noticed an increase in interest in attendance monitoring in Universities recently, probably not unrelated to the UKBA’s withdrawal of London Metropolitan University’s trusted sponsor status. Throughout my career in HE, both as a student and staff, attendance has never really been compulsory, certainly not at lectures. Yet, there’s some evidence in the literature that students aren’t completely opposed to the idea. (Though they’re not wildly enthusiastic either.) See for example

NEWMAN-FORD, L., FITZGIBBON, K., LLOYD, S. and THOMAS, S., 2008. A large-scale investigation into the relationship between attendance and attainment: a study using an innovative, electronic attendance monitoring system. Studies in Higher Education, 33(6), pp. 699-717.

or

MUIR, J., 2009. Student attendance: Is it important, and What Do Students Think? CEBE Transactions, 6(2), pp. 50-69

Those are relatively small scale studies (There don’t seem to be any large scale studies, or if there are, I’ve missed them.) Outside the literature too, there’s some evidence that the issue is becoming significant. A web trawl found this post on a hyperlocal news blog in Newcastle which, when you look at the results doesn’t quite support the writer’s claim of “overwhelming rejection”. The rejection is of one particular model of monitoring. It would be very interesting to know how many other student unions have held similar referenda (and how they turned out). There’s also an interesting case in Texas where a school student has recently lost her case against her school district using an RFID chip to monitor her attendance.

To get back to HE though I did do a crude trawl of every UK university web site, to get a sense of what institutions were doing, and there are a small number of institutions (South Bank, Huddersfield, East London, and ironically enough, London Metropolitan) that do claim to have active electronic monitoring systems in place, although much more detailed research would be needed to assess the extent to which they are deployed in practice. There were a great many more institutions whose web sites linked to policy statements and papers which implied that they should do something about it. Over half the sites were silent on the topic, although web sites are a very limited source of data.

But, if this is a reaction to the Border Agency, it seems something of an over-reaction. I had a look at the Border Agency’s web site and they don’t require institutions to monitor attendance in the sort of detail that the South Bank system seems to be able to facilitate. All they require is that students are monitored at particular points in their academic career.

I’m not implying here that any institution is reacting inappropriately to the UKBA. There are good reasons to monitor student attendance. The articles I mention above draw on literature that suggests the existence of a correlation between attendance and academic attainment, although one would expect that stronger students would be more likely to attend classes. More compellingly it would certainly generate a great deal of useful planning data for universities, and I suspect it would “encourage” students to attend. While monitoring attendance of students is not the same as compelling them to attend, the existence of a monitoring programme would likely give the impression of compulsion. (And there are strong arguments against compulsion, which I will not rehearse here, except to point out that some elements of an educational experience are inherently compulsory. You can’t be assessed if you don’t present yourself, or at least your work, for assessment.)

It should also be acknowledged that a University education consists of rather more than lectures and seminars, which also raises some interesting questions. Should art schools monitor time spent in studios? What about virtual education? Does logging into the computer count as attending? Why not, if physical presence is the only measure of attendance in the “real” world? After all it’s quite possible to be physically present and mentally absent, as I can testify from personal experience. This is clearly a topic around which I’m going to have to put my thoughts in order. If anyone is doing any research in this area, please do comment.

What is digital scholarship?

I’ve been wondering about the phrase “digital scholarship” recently and what it might mean. I think we have to start by asking why is “digital scholarship” different from “scholarship”? (If it isn’t different, why are we worrying about it?). For me, scholarship is the attempt to conceptualise and theorise about the real world. That’s not quite the same as “learning”, although that is an important subdivision. My definition presents a problem though, since, as far as science has been able to discover, the only place conceptualisation and theorisation can occur is inside the human mind. So what then is “digital scholarship?” These are very much preliminary thoughts but three elements leap out at me, namely metadata, critique, and accessibility.

Scholarship has always been dependent on inputs and outputs, whether oral stories, printed or written texts, plays, experiences or, video productions. It is these that computers are excellent at managing, and I think that is where the notion of “digital scholarship” has arisen – but that’s not quite the same as my definition of scholarship. Yes, computers offer tools that scholars can use to work together to combine their work, but a blog entry, a wiki page, or even a tweet is still a snapshot of the state of a human mind at a given point, and that mind is, even as it is writing, simultaneously considering, accepting, rejecting or developing concepts.

So what is it that makes “digital scholarship” scholarship? (We can all agree that computers make scholarship “digital”, so I’m going to take their role as read in this post, although there’s clearly a lot of innovative work that can be done with them, and there might well be a scholarship emerging in this area.) In then end, I think it comes down to the outputs and inputs (although any artefact, digital or not, can be both input and output depending on how it is used). But an important quality of these artefacts is that they are inanimate. That means that they can only be accessed through metadata. Yes, they can be changed, but unlike a mental concept they are not changed by immediate experience, nor can they question themselves. That means digital scholarship must concern itself with this, since digital artefacts are less visible. The sort of intellectual serendipity you get from wandering around a library is hard to replicate in a digital environment. There are some metadata tools (e.g. RSS, and some of the work going on around games, virtual worlds and simulators) that are qualitatively different from analogue tools and can alert users to relevant concepts, but they’re still reliant on an accurate description of the data in the object itself, which leads into the second of my three aspects, critique

There is a second quality about digital artefacts, and one that is easy to miss. Much as we like to convince ourselves that they, especially “open” ones, are free, they are, and will always remain commodities and as such still subject to the exchange relations inherent in a capitalist society. No-one would seriously dispute that a book has an exchange value, however small.. Digital artefacts too are the product of human labour and thus contain an element of the surplus value that that creates, albeit arguably much smaller .While money might not be being exchanged for that value, that doesn’t negate the argument. The things being exchanged are among other things, the author’s reputation, further labour potential to improve the product and of course a small element of the labour inherent in the production of the hardware, software and server time necessary to use the artefact. Essentially an open digital artefact is an unfinished product. Which means the second area of concern for digital scholarship is critique. Critique has always been an essential aspect of scholarship, but the absence of peer review in digital production makes it much more important.

Finally, there is the question of accessibility. By “accessibility” I mean the ways in which users use a technology. Clearly, there are some physical, social and economic barriers to using a technology, and any serious scholarship has to concern itself with the potential for exclusion that those barriers present. But digital technologies also offer multiple ways of doing things and human beings, being what they are inevitably find ways of using new tools to do things in unexpected ways, ways which may appear “wrong” to the original provider. (It is, of course true that sometimes these ways of doing things are actually wrong – in which case the user has to either seek assistance or give up) Since learning often involves making mistakes, I’m not comfortable with phrases like “digital literacy” if that means “doing things in the way we, as content producers, think they should be done”. So I’d argue that digital scholarship has to concern itself with the issue of accessibility in its broadest sense, much as traditional scholarship has concerned itself with issues of publication.

So, for me digital scholarship shares many values and ideas with traditional scholarship but places a greater emphasis on how ideas are described and accessed, and needs to be even more sceptical of the validity of expressed ideas, and much more involved with how people use technology. The next question to ask is what that would look like in practice. But that’s for another day.

Should universities monitor student attendance?

The recent withdrawal of Highly Trusted Sponsor Status by the United Kingdom Border Agency (UKBA) from London Metropolitan University in September 2012 has raised some questions in my mind about practices surrounding attendance monitoring in higher education. Let’s be clear about this though. London Met lost its status because it had, according to the UKBA sponsored students who did not have leave to remain in the UK, not primarily, because it was failing to record attendance. (Although press reports imply that it was in fact failing to do so)

Nevertheless, it is a requirement of the UKBA that universities who wish to sponsor students on a visa must make two “checkpoints” (re-registrations) within any rolling 12 month periods and to report any student who misses 10 consecutive expected contacts without reasonable permission from the institution. Any such report must be made within 10 days of the 10th expected contact. The nature of such contacts is left to the institution although the UKBA suggests as examples, attending lectures, tutorials, seminars, submitting any coursework, attending any examination, meetings with supervisors, registration or meeting with welfare support. In order to ensure compliance sponsors may be asked to complete a spreadsheet showing the details of each student sponsored and their attendance. This spreadsheet must be provided within 21 days of the request being made (UKBA, 2012). (Taken from http://www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk/sitecontent/documents/employersandsponsors/pbsguidance/guidancefrom31mar09/sponsor-guidance-t4-060412.pdf?view=Binary accessed 17/09/12)

As I said, at the start of the post, this raises some questions in my mind. I’ve had a longish career in higher education, but, apart from those courses which are sponsored by external bodies, notably the NHS it is actually rather rare in my experience for student attendance to be consistently monitored. It may not have been an issue. Students are adults after all, and perfectly free not to take up what they have paid for, and there appear to be few empirical studies of attendance monitoring in the United Kingdom. There is, in contrast, a huge literature on retention, unsurprising given the cost of early withdrawal to both institutions and students, and one would expect that failure to attend teaching events is an obvious early warning sign. Most scholarly attention seems to have been focussed on establishing the extent of a correlation between attendance and student performance, which does seem to exist (Colby, 2004). There has never been a consistent sector wide approach to monitoring the attendance at classes of students enrolled on University degree and post degree courses. The border agency farrago seems to me to have raised the importance of this issue for he following reasons:

- If universities only monitor the attendance of overseas students they could be accused of discriminating against them, or, if Colby is correct about a correlation, in favour of them.

- If that correlation does exist then it is in universities interests as organisations, to monitor attendance since better performance from students will give them higher positions in university league tables, making them more attractive to potential students.

- For that reason, it ought to be in the interests of their students to have their attendance monitored, or, more accurately to have their absences noted and investigated. As far as I know, there has never been a large scale sector wide survey of attendance monitoring practices. (Possibly because there aren’t very many such practices.)

I have carried out a very preliminary survey of every UK university web site to see what in fact Universities are doing about attendance monitoring. This should be regarded with extreme caution. I haven’t included the full findings here because web sites are not definitive proof and it is not possible to draw any firm conclusions. Just because a university does not publish its attendance policy does not mean it does not have one. The reason for doing the web site survey was to get a sense of the extent of the problem and indicate a potential sampling strategy to identify areas for further detailed research. Bearing that in mind, it appears that nearly all of them delegate responsibility for attendance monitoring to individual departments. About half claim to have any sort of university wide attendance policy, and the content of these policies very dramatically (but even so, departments are still responsible for implementing) but only a very small number actively monitor attendance for all or most students. Practices vary from occasional attendance weeks where pretty much everything is monitored during those weeks (Durham), to advanced technological systems which read student cards (London South Bank). Here at Lincoln practice appears to be sporadic. Many colleagues use paper sign-in sheets, something we do in my own department, but it is fairly unusual for this data to be entered into any sort of database. It seems to be filed away somewhere, and ultimately, thrown away, which seems a rather strange practice!

So the answer to my question in the title is “I don’t know, but there does appear to be a case to investigate it further”.

Reference

Colby, J. 2004. Attendance and Attainment, 5th Annual Conference of the Information and Computer Sciences – Learning and Teaching Support Network (ICS-LTSN), 31 August–2 September, University of Ulster. http://www.ics.heacademy.ac.uk/italics/Vol4-2/ITALIX.pdf (accessed 15/10/2012)

Electronic Submission of Assignments part 2

As promised here’s part 2 of my report on the E-submission event held at Manchester Metropolitan University last Friday.

The presentations from the event are available here; – http://lncn.eu/cpx5

First up was Neil Ringan, from the host university talking about their JISC funded TRAFFIC project. (More details can be found at http://lrt.mmu.ac.uk/traffic/ ) This project isn’t specifically about e-submission, but more concerned with enhancing the quality of assessment and feedback generally across the institution. To this end they have developed a generic end to end 8 stage assignment lifecycle, starting with the specification of an assessment, which is relatively unproblematic, since there is a centralised quality system describing learning outcomes, module descriptions, and appropriate deadlines. From that point on though, practice is by no means consistent. Stages 2-5; Different practices can be seen in setting assignments, supporting students in doing them, methods of submission, marking and production of feedback. Only at stage 6, the actual recording of grades, which is done in a centralised student record system does consistency return. Again we return to a fairly chaotic range of practices in stage 7, the way grades and feedback is returned to student. The Traffic project team describe stage 8 as the “Ongoing student reflection on feedback and grades”. In the light of debating whether to adopt e-submission, I’m not sure that this really is part of the assessment process from the institution’s perspective. Obviously, it is from the students’ perspective. I can’t speak for other institutions, but this cycle doesn’t sound a million miles away from the situation at Lincoln.

For me, there’s a 9th stage too, which doesn’t seem to be present in Manchester’s model, which is what you might call the “quality box” stage. (Perhaps it’s not present because it doesn’t fit in the idea of an “assessment cycle”!) I suppose it is easy enough to leave everything in the VLE’s database, but selections for external moderation and quality evaluation will have to be made at some point. External examiners are unlikely to regard being asked to make the selections themselves with equanimity, although I suppose it is possible some might want to see everything that the students had written. Also of course how accessible are records in a VLE 5 years after a student has left? How easy is it ten years after they have left? At what point are universities free to delete a student’s work from their record? I did raise this in the questions, but nobody really seemed to have an answer.

Anyway, I’m drifting away from what was actually said. Neil made a fairly obvious point (which hadn’t occurred to me, up to that point) that the form of feedback you want to give determines the form of submission. It follows from that that maybe e-submission is inappropriate in some circumstances, such as the practice of “crits” used in architecture schools. At the very least you have to make allowances for different, but entirely valid practices. This gets us back to the administrators, managers and students versus academics debate I referred to in the last post. There is little doubt that providing eFeedback does much to promote transparency to students and highlights different academic practices across an institution. You can see how that might cause tensions between students who are getting e-feedback and those who are not and thus have both negative and positive influences on an institutions National Student Survey results.

Neil also noted that the importance of business intelligence about assessments is often underestimated. We often record marks and performance, but we don’t evaluate when assessments are set? How long are students given to complete? When do deadlines occur? (After all if they cluster around Easter and Christmas, aren’t we making a rod for our own back?) If we did evaluate this sort of thing, we might have a much better picture of the whole range of assessment practices.

Anyway, next up was Matt Newcombe, from the University of Exeter to tell us about a Moodle plugin they were developing for e-assessment More detail is available at http://as.exeter.ac.uk/support/educationenhancementprojects/current_projects/ocme/

Matt’s main point was that staff at Exeter were strongly wedded to paper-based marking arguing that it offered them more flexibility. So the system needed to be attractive to a lot of people. To be honest, I wasn’t sure that the tool offered much more than the Blackboard Gradebook already offers, but as I have little experience of Moodle, I’m not really in a position to know what the basic offering in Moodle is like.

Some of the features Matt mentioned were offline marking, and support for second moderators, which while a little basic, are already there in Blackboard. One feature that did sound helpful was that personal tutors could access the tool and pull up all of a student’s past work and the feedback and grades that they had received for it. Again that’s something you could, theoretically anyway, do in Blackboard if the personal tutors were enrolled on their sites (Note to self – should we consider enrolling personal tutors on all their tutees Blackboard sites?).

Exeter had also built in a way to provide generic feedback into their tool, although I have my doubts about the value of what could be rather impersonal feedback. I stress this is a personal view, but I don’t think sticking what is effectively the electronic equivalent of a rubber stamp on a student’s work is terribly constructive or helpful to the student, although I can see that it might save time. I’ve never used the Turnitn rubrics for example, for that reason. Matt did note that they had used the Turnitin API to simplify e-marking, although he admitted it had been a lot of work to get it to work.

Oh dear. That all sounds a bit negative about Exeter’s project. I don’t mean to be critical at all. It’s just that it is a little outside my experience. There were some very useful and interesting insights in the presentation. I particularly liked the notion of filming the marking process which they did in order to evaluate the process. (I wonder how academics reacted to that!)

All in all a very worthwhile day, even if it did mean braving the Mancunian rain (yes, I did get wet!). A few other points were made that I thought worth recording though haven’t worked them in to the posts yet.

• What do academics do with assignment feedback they give to theire current cohort? Do they pass on info to colleagues teaching next? Does anybody ever ask academics what they do with the feedback they write? We’re always asking students!

• “e-submission the most complex project you can embark on” (Gulps nervously)

• It’s quite likely that the HEA SIG (Special Interest Group) is going to be reinvigorated soon. We should joint it if it is.

• If there is any consistent message from today so far, it is “Students absolutely love e-assessment”

Finally, as always I welcome comments, (if anyone reads this!) and while I don’t normally put personal information on my blog, I have to go into hospital for a couple of days next week, so please don’t worry if your comments don’t appear immediately. I’ll get round to moderating them as soon as I can

Electronic Submission of Assignments: part 1

All Saints Park, Manchester Metropolitan University

On Friday I returned to my roots, in that I attended a workshop on e-submission of assignments at Manchester Metropolitan University, the institution where my professional career in academia started (although it was Manchester Polytechnic back then). The day was a relatively short one, consisting of four presentations, followed by a plenary session. That said, this is a rather long blog post because it is an interesting topic, which raises a lot of issues so I’m splitting it into two in order to do it full justice. I’m indebted to the presenters, and the many colleagues present who used their Twitter accounts for the following notes (if you wish to see the data yourself search Twitter for the #heahelf hashtag).

The reason I went along to this is because there is a great deal of interest in the digital management of assessment. One person described it as a “huge institutional wave about to break in the UK”, and I think there is probably something in that. How far the wave is driven by administrative and financial requirements, and how far by any pedagogical advantages it confers was a debate that developed as the day progressed.

The first presenter, Barbara Newland, reporting on a Heads of E-learning commissioned research project offered some useful definitions.

| E-submission | Online submission of an assignment |

| E-marking | Marking online (i.e. not on paper) |

| E-feedback | Producing feedback in audio, video or on-line text |

| E-return | Online return of marks. |

(Incidentally, Barbara’s slides can be seen here: http://www.slideshare.net/barbaranewland/an-overview-of-esubmission)

While the discussions touched on all of these, the first, e-submission, was by far the dominant topic. The research showed a snapshot of current HE institutional policy, which indicated that e-submission was much more common than the other three elements, although it has to be said that very few UK institutions have any sort of policy on any aspect of digital assignment management. Most of the work is being done at the level of departments, or by individual academic staff working alone.

Developing an institutional policy does require some thought, as digital management of assessment can affect nearly everyone in an institution and many ‘building blocks’ need to be in place. Who decides whether e-submission should be used alone, or whether hard copies should be handed in as well? Who writes, or more accurately re-writes, the university regulations? Who trains colleagues in using the software? Who decides which software is acceptable (Some departments and institutions use Turnitin, some use an institutional VLE like Blackboard or Moodle, and some are developing stand-alone software, and some use combinations of one or more of these tools)

A very interesting slide, on who is driving eSubmission adoption in institutions raised some the rather sensitive question of whether the move to e-assessment is being driven by administrative issues rather than pedagogy? The suggestion was that the principal drivers are senior managements, learning technologists and students, rather than academic staff and this theme emerged in the next presentation, by Alice Bird, from Liverpool John Moores University, which seems to be one of the few (possibly the only) UK HEIs that has adopted an institution wide policy. Their policy seems to be that e-submission is compulsory if the assignment is a single file, in Word or PDF format and is greater than 2000 words in length. Alice suggested that for most academic staff, confidence rather than competence had proved to be the main barrier to adoption. There was little doubt that students had been an important driver of e-submission, along with senior management at Liverpool One result of this was a sense that Academics felt disempowered, in that they had less control over their work. She also claimed that there had been a notable decline in the trade union powerbase relative to the student union. Of course, that’s a claim that needs unpicking. It seems to me that it would depend very much on how you define “power” within an institution, and the claim wasn’t really backed up with evidence. Still, it is an issue that might be worth considering for any institution that is planning to introduce e-submission.

Although there were certainly some negative perceptions around E-submission at Liverpool, particularly whether there were any genuine educational benefits, Alice’s advice was to “just do it”, since it isn’t technically difficult. As a colleague at the meeting tweeted the “”Just doing it’ approach’ has merits in that previously negative academics can come on board but may also further alienate some”. I think that’s probably true, and that alienation may be increased if the policy is perceived as having predominantly administrative, as opposed to educational, benefits.

She did point out that no single technological solution had met all their needs, and they’d had to adapt, some people using the VLE (Blackboard, in their case), some using Turnitin. What had been crucial to their success was communication with all their stakeholders. Certainly e-submission is popular with administrators, but there are educational benefits too. Firstly feedback is always available, so students can access it when they start their next piece of work. Secondly, electronically provided feedback is always legible. That may sound a little facetious, but it really isn’t. No matter how much care a marker takes with their handwriting, if the student can’t read it, it’s useless. Thirdly, students are more likely to access their previous work and develop it if it’s easily available.

There are tensions between anonymous marking and “feedback as dialogue”, some tutors arguing that a lack of anonymity is actually better for the student. Other difficulties, in spite of the earlier remarks about confidence, was some confusion over file formats, something we’ve experienced at Lincoln with confusion between different versions of Word. As another colleague, suggested this is a bit of a “threshold concept” for e-submission. We can’t really do it seamlessly, until everyone has a basic understanding of the technology. I suppose you could say the same about using a virtual learning environment like Blackboard. Assessment tends to be higher stakes though, as far as students are concerned. They might be annoyed if lecture slides don’t appear, but they’ll be furious if they believe their assignments have been lost, even if they’ve been “lost” because they themselves have not correctly followed the instructions.

There was also a bit of a discussion about the capacity of shared e-submission services like Turnitin to cope, if there was a UK wide rush to use them. (Presumably it wouldn’t just come from the UK either). There have certainly been problems with Turnitin recently, which distressed one or two institutions who were piloting e-submissions with it more than somewhat!

The afternoon sessions, which I’ll summarise in the next post focussed on the experience of e-submission projects in two institutions, Manchester Metropolitan University and Exeter University.

Blackboard 2012+

Here’s a little more from Wednesday’s Midlands Blackboard User Group meeting. As always, Blackboard representatives were present at the meeting to tell us all about their plans for the future, and this proved an interesting session. As a company they have always had a strategy of absorbing, or partnering with other tools, but I was quite surprised to hear that they are talking about integrating with Pebble Pad, which I’ve always felt was the best of the various e-portfolio tools available. My surprise arises from the fact that Pebble pad is a product that has always had a completely different look and feel from Blackboard, although I haven’t seen the latest versions as yet. Colleagues from other institutions tell me they’re very impressive though. They also mentioned a potential partnership with a company called Kaltura, who offer a video management tool which has apparently enjoyed some success in HE.

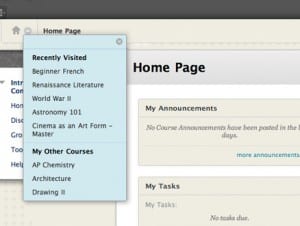

On to more mundane matters, we were told about the upcoming service packs. Service packs are not new versions of the software, but are either enhancements to the existing functionality of the software, or fixes for the enhancements that didn’t quite work in the previous version. The latest such pack is, according to Blackboard, the first one to be wholly based on customer feedback, and offers a number of significant improvements to the user interface. Most importantly they have finally got rid of the module boxes on the front page in this pack, replacing them with a menu that appears when you roll your cursor over the word “courses”. There’s a “recently visited” list of modules too. Instructors can change colour schemes within modules, although there is a limited range of schemes. Finally they have introduced what they call course relationships – this simply means that it is possible to arrange menus hierarchically, so for example, you could show modules as part of a programme.

In terms of assessment, they have introduced negative and weighted marking into the on-line quizzes. Although there’s some debate about this, my own feeling is that the ability to penalise students for guessing makes a multiple choice test a much more powerful assessment tool. There’s also a regrade the whole test feature. Previously, if an instructor made an error and indicated an incorrect answer as correct, then they had to regrade each students attempt. Now this can be done in a single operation.

The final enhancement in the latest service pack is what is called “standards alignment” It is possible to align course and even specific learning outcomes with sets of standards, and you can also find content that is associated with particular standards, a feature that looks as though it may be particularly useful in course validations, as we’ll be able to test how any proposed module meets the strategic requirements of the university (In theory. Of course, it would be necessary to convert those requirements into standards first)

For techies, Out of box shibboleth and CAS authentication will be provided and it is now possible to use whatever version of Apache you want. Finally, “Blackboard Analytics” will be released in June, which offers very detailed statistical reporting, although this is a new product, not part of a service pack.

This last paragraph looks at medium term plans, although the Blackboard representative did admit that most of this stuff was as yet, only half written. However it does sound quite exciting. Plans for later service packs (2013) include a much greater social presence for Blackboard, including a student learning space, where they can interact with friends (I detect the influence of Facebook here), Something else that is long overdue is a shareable learning object repository which will be added to the content store. They’ll also be upgrading the test canvas again, to make some of the question tools a little bit more user friendly. The survey tool will also be enhanced so that it will be possible to deploy surveys outside Blackboard, which may be of some interest to researchers. Analysis tools will be provided within Blackboard. Finally, and again something that should have been done years ago, it sounds as though it will be possible to integrate the Blackboard Calendar with web based calendars (although they didn’t mention Outlook).

You must be logged in to post a comment.