We’re developing a bit of a tradition of “thinking aloud” here at Lincoln,meaning ruminating on an issue in a public forum, to kick start debates on research ideas, and this post is part of that. It shouldn’t be taken as a definitive proposal, just something that I’m thinking about.

Anyway, I’ve been reading a fascinating book on the Politics of Technology, (Harbers, (ed.), 2005) which contains a number of contributions arguing that non human technological artefacts have more agency than they are often given the credit for. Several of the contributors describe the political contradictions inherent in certain medical screening technologies. By “political” I mean dispositions of power – who really makes choices about how they act. One of the examples given is of a pregnancy screening test which alerts women to the likelihood of giving birth to a child with Down’s Syndrome. One the one hand, that could be interpreted as giving pregnant women more freedom. They have the choice of terminating the pregnancy, or continuing with it, and preparing to care for a child that is likely to suffer from a severe disability. On the other hand there is an argument that the screening service itself makes it more likely that women will choose to terminate their pregnancies because by using words such as malformations and disorders in their research, the designers will have played a part in normalising “a society in which the chance of having a disabled child is no longer perceived as natural” (p234) That raises the question of the extent to which the technology (the test) has any agency of itself – surely it is the designers of the technology who give it agency.

There’s a little more to it than that of course – the test has to become routinely, or at least widely available, for such normalisation to occur. The fascinating question is how far is that agency co-opted by the different groups of users. In fact this particular chapter goes on to discuss how parliamentarians and medical professionals in the Netherlands took a very different view of how the test was to be used, but you’ll have to read the book for that discussion.

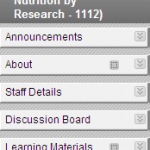

So what any of this has to do with Blackboard, or any learning technology. Well, it crossed my mind that a virtual learning environment shares some of the social characteristics of a medical technology. Effectively we’re designing something to facilitate something that other practitioners will use, and in the way we’re implementing it making implicit decisions about how it will be used. We decided for example to have a set of six default buttons on our Blackboard sites,

, thus normalising the idea that a learning experience requires “Announcements”, “staff details”, “about”, “learning materials”, a “discussion group” and “assessments”. The really interesting question is why did we think this was appropriate? It certainly doesn’t match our “student as producer ” strategy as all of these (except the discussion board) have a rather didactic cast to them.

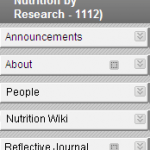

These are default settings, and instructors can amend them there was clearly a political dimension to the decision to set them in the way we did. It was based on what we understood as the way teaching went on in the university. But, if student as producer is to take off, then the future defaults might look like the illustration on the right. (click both illustrations to open them in full)

Student as producer doesn’t remove the teacher from the process, rather renders learning a process of co-production (another theme running through the Harbers book). So we’d probably still want to provide a facility for making announcements (but we might want to allow students to do it too), we’d want to provide staff details, (and student details) and at a pinch a course handbook. We’d probably want to keep assessments too. But Learning Materials and the discussion board, might be replaced by a Wiki, and why shouldn’t there be buttons for public blogs and private reflective journals.

Also of course, this ignores a very important question. Why use a VLE at all. Blackboard, and other corporate providers are not without their critics. They’re expensive, can be restrictive (although I suppose that could, in theory, be mitigated by sensitive implementation). On the other hand, there are wide variations in the ability of university lecturers to cope with technology. (Among students too – I don’t really buy the “digital natives” idea). For all Blackboard’s faults, it does sort of “hold the hand” of those who are less confident with the technology. There’s clearly a potential for some research here. How many of our own staff have gone beyond the default settings? What do other institution’s default settings look like? How many of their staff have pushed those boundaries. How many would want to? I’ve been talking about Blackboard, but of course we, and many other institutions have staff who choose to use other systems, or none at all. Clearly this is too much for a single blog post, so I’ll no doubt be returning to this topic in future posts

HARBERS, H., 2005. Inside the politics of technology agency and normativity in the co-production of technology and society. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.