Durham Conference blog post, part 3

As promised, here’s the last blog post from Durham, but in some ways the most controversial. There was a panel debate at the end of the first day on whether institutions should impose a minimum standard on VLE provision. To put it in Lincoln terms do students have a right to expect that certain things should be provided on Blackboard? This is an issue that raises its head from time to time, and on the face of it one might think it was uncontroversial. (Students are paying fees, are they not? Why shouldn’t they expect some material to be provided through what is, effectively, the major student learning portal.).

For me though these things aren’t quite so simple. I do accept that students do have a right to a basic institutional information set, but there’s a debate to be had about what it should contain. I’m a lot less comfortable with the notion that every module, across all disciplines and at both undergraduate and postgraduate level should be denied the freedom to use a technology in whatever way those teaching the module think most appropriate. My second objection to a minimum standard of teaching information is that it is very likely to be highly didactic effectively saying “This is what you must do to pass this module.”Lincoln’s strategy is to cast the student as a producer of their own learning. While that clearly involves providing students with spaces to learn in, and access to resources, whether they be text based, digital, or specialised equipment, it also involves providing the opportunity to make, show, and perhaps most importantly of all discuss their work. I’m not sure that VLE’s are really set up for that as I said in a post a few weeks ago. Not yet, anyway.

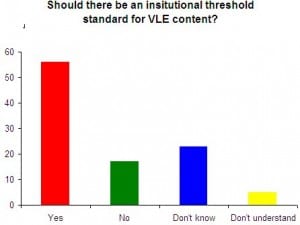

Anyway, that’s enough about my views – how did the debate go.? Well, right at the beginning, we had a vote on whether we should have a minimum standard, and the results were

YES – 56%

NO – 17%

DON’T KNOW – 23%

DON’T UNDERSTAND THE QUESTION – 5%

(Actually, the preferred term is threshold standard rather than minimum standards, the idea being that users will progress beyond the threshold, rather than work to the minimum).

In some respects this debate is a reflection of the success of the VLE. Many of the early adopters were seen as being rather adventurous, pushing the boundaries of what could be done with technology. Nowadays though, VLEs , and learning technology are commonplace, and while I don’t want to over – generalise, students are generally much more familiar with learning technologies, which implies that there would be a demand for technology based learning even if fees had not been introduced. The environment they grew up in and are familiar with happens to be technology rich. Certainly, as one of the panellists suggested, it’s a good idea to try and look at the VLE through students’ eyes. I haven’t conducted any sort of survey into this, but I strongly suspect that most educational developers prefer to see themselves as having a quality enhancement role, rather than a quality assurance role. Enhancement, to be effective, must involve the views of the users, which takes us back to the Student as Producer strategy.

Some contributors suggested that the commonest complaint from students were not so much about content, but about inconsistencies in design and structure. That, as one panellist pointed out was a real problem for joint honours students. The general feeling of the meeting was that this is best solved by involving students in the design but at a course or departmental level, rather than an institutional level, which would go some way to alleviating my objection that courses in say Fine Art, are profoundly different from courses in Computer Science and trying to impose a universal standard on both would be counter productive. (Although that still wouldn’t really help joint honours students) It was suggested that departments could produce mutually acceptable templates for their Blackboard sites, which is a start, but still runs the risk of empty content areas. I’m not sure that’s a major issue. While we don’t mandate what staff do with their Blackboard sites at Lincoln, we do have a standard template for new sites, which staff are free to change. My feeling is that, while I have some reservations about the didactic nature of the template, it does work quite well, although I do think there’s scope for a small piece of internal research assessing how often colleagues depart from the template, or if they don’t which buttons are most used.

One audience member asked about standards in other technologies. I’m not sure that, other than computer use regulations, which are really about ensuring that an institution complies with legal requirements, they are that common. We don’t really mandate what colleagues can say in e-mail, or even what format emails should be sent in. Even if we did, we couldn’t enforce it, which is of course an issue for VLE provision too. The only real sanction is that poorly designed content posted on a VLE is likely to stay around much longer than a poorly delivered lecture, and be visible to colleagues) which ought to be an incentive for colleagues to concentrate on ensuring that such material was of the best possible quality.

A final objection to a threshold standard is that it requires a certain standard of competence from the users of the technology. University lecturers are primarily employed for their disciplinary expertise, and to a lesser extent for their pedagogical skill. Technological skill comes (at best) third, although you might argue that, in the current highly technological environment, digital literacy is as essential as, well, literacy. My own view is that most people’s digital literacy is pretty much adequate, although there are a minority who will always prefer to get someone else (usually an admin assistant) to post material on the VLE. That I think is where minimum and threshold standards have the potential to cause recruitment problems. As an institution we’d have to decide what were essential skills for working with technology, and ensure that we find people who had sufficient disciplinary, pedagogical and technological skills.

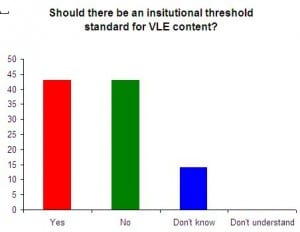

Interestingly when the vote was run again at the end of the session, the results were

YES – 43%

NO – 43%

DON’T KNOW – 14%

DON’T UNDERSTAND THE QUESTION – 0%

Which if nothing else, indicates that debating a topic improves understanding. At the end, everybody understood the question. More seriously, the debate was an excellent illustration of the problems associated with imposing standards on a highly diverse community. They’re a good idea until you have to conform to them yourself.

One last thing – there’s a much better summary of the debate available provided by Matt Cornock, to whom many thanks.

All that remains for me to do is to thank the Learning Technologies team at Durham for organising an excellent conference, (which they always do!) and to recommend the conference to colleagues for next year. It’s always a good mix of academics and educational developers, and you get to see some really interesting practice from around the sector. I’ve been for the last four years now, and while I’m more than happy to keep my attendance record up, I’m beginning to feel a bit selfish about hogging it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.