The other day, I braved the elements and took a trip to Birmingham University Medical School in order to attend the Midlands Blackboard User Group. This is quite a useful way of getting to find out what colleagues in other local universities are up to, and indeed to find out what Blackboard’s plans are. On this occasion, it seemed to be a little less well attended than usual, which was probably related to the weather. To make matters worse I wasn’t feeling at my best, so I probably didn’t get as much out of it as I usually do. Still, it wasn’t without interest.

First up was Alistair Brook (Blackboard Collaborate) to talk about the incorporation of Wimba and Elluminate into the product – there’s a nice introduction here (needs Flash) which tells you what Wimba can do. Essentially it’s a way of adding relatively rich media to Blackboard, and providing online tutorial support to remote students. While it is expensive, we do have to consider how much, for example, the recent weather related snow closures cost the university. Of course, users need web cams and microphones to participate but the hardware costs are relatively low.

Alistair argued that in fact there were very few universities not using any collaboration tool at all, and talking to colleagues, most of them do in fact appear to be making some limited use of these things. Another quite interesting aspect, (which is something Blackboard, who have recently acquired Wimba, seem to be pushing is emphasising the potential for using these tools in a cross institutional role. That is, using it for what we might call administrative support, which we’ve always tended to use the Portal for. Reading between the lines, I wonder if Blackboard are going for the Sharepoint market, although I must be clear that nobody said anything along those lines. We’ve always said that Blackboard is a “teaching and learning” tool and have resisted adopting it as a more general portal. That might be more convenient for us, but from a student point of view, it certainly makes sense to have single points of contact for students and I am coming round to the view that Blackboard may be a rather more effective communication system than Sharepoint. Clearly, we’d need to do a lot of work, (and spend a lot of money) on thinking this through before making any decisions, and there’s no getting away from the fact that the problem with the Portal is less to do with the technology and more to do with weak information management (no version control, different departments putting different versions of the same story, in slightly different places). Blackboard are keen to push the technology as a tool for engaging with first years etc, and identifying those students that are at risk of dropping out. (But, in order to do that, there had better be someone on the other end. I suppose that’s an example of technology changing working practices)

As Alistair said, Blackboard are planning to create a more integrated product, which they are calling Project Gemini. (Which isn’t going to be the product name.) The reason is that they believe student experience & expectations are more diverse, students will be entering worst employment market in 30 years, there are increased business/industry expectations of university graduates. Students use technology every day, they’ll be leaving with huge debt. As a consequence they’ve been looking at the technology first year students bring with them and how they use it. Project Gemini is the result of this – they want a system that is much more mobile friendly, and multimedia oriented.

One slightly more controversial point was that given that HE is likely to become price sensitive can we justify charging an extra tenner for technology access? I guess BB would quite like it if we did, although, to do that we’d have to become a genuinely private sector institution, rather than reliant on state subsidy through student loans.

Getting back to the point, I raised the issue that collaborative seminars are a good idea in many ways, but they can easily shut out the less articulate or confident. That’s not a reason not to find ways of doing them and reducing that of course, but I seemed to get a standard issue answer that universities needed to be more efficient, and that we had to find ways of linking strategy and technology. Which we do, but there was quite a lot of scepticism about the reliability of the technology. Especially out in the field which raises further issues about what we are doing about planning for poor infrastructure in the future? (e.g how can we provide advice for users to check their computer, or if it’s not up to standard, what alternatives can we provide?) That is our responsibility.

It struck me that all this had a clear value for the sort of curricula offered, for example, at Holbeach – but I’m a bit more sceptical about the value of these tools for on-campus use. The presenter’s answer to that was inevitably “snow” (and later, Icelandic volcanoes). And I guess closing the university did probably cost more than a subscription, although I’m also fairly sure, that there’d be a large proportion of staff and students who wouldn’t know how to use it – there’s probably an element of strategic incompetence in that. But, I’d have been prepared to run the PGCE session that was cancelled as a webinar if we’d had the technology. And there’s a lot of value in the ability to record lectures, Wimba video is not streamed but chunked into 2 minute segments. (Can be linked to slides, as in Echo 360 which I’ve blogged about before) Amusingly the presenter didn’t seem to understand why students would want to look at a portion of a lecture, rather than the whole thing. (Until we explained it to him)

- Chat

- Audio conferencing

- Video conferencing

- Desktop sharing

- Whiteboard

- Virtual Classroom

There then followed a brief discussion of other collaborative technologies that are out there. Northampton, for example, were informally supporting Skype, but there was an interesting point made that if you’re charging students for a free service (e.g. Second Life) (as we might have to do) then you have no control over what you’re providing, and you won’t be able to fulfil your contract. Well, of course, Blackboard would say that wouldn’t they? But it doesn’t make it any less true.

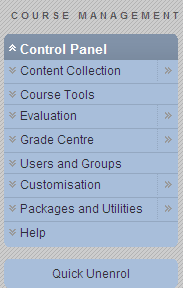

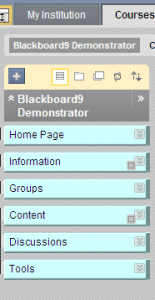

The afternoon session was devoted to the support that Blackboard offered. Frankly this was of more interest to technical support staff, than to user support staff, and was largely concerned with upgrading to version 9.1 (If you’re interested they provide a web site here: http://www.blackboard.com/upgradecenter. which offers Webinars, documentation, Upgrade kits which tell you what you need to look for. There’s also an on demand learning centre at http://Ondemand.blackboard.com containing vver 90 resources which show you how to use different parts fo the system – and you can use them to introduce staff to BB9.1. Finally there’s “Behind the Blackboard”, which is more for technical support staff http://behind.blackboard.com. If you have a question about Blackboard you can post it on Behind the Blackboard. It’s not just for problems but for any detailed question, There’s also a knowledge base which may prevent you needing to ask the question in the first place. Questions are ticketed so you can follow the progress of your ticket. However, there are only two accounts per institution on Behind the Blackboard though. An interesting sign of the times is that Blackboard moving their European Support team from Amsterdam to Sofia. We don’t yet know what effect, if any, this will have on support.

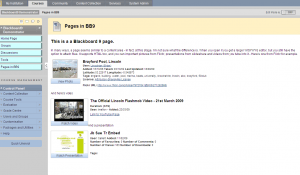

Finally, they admitted that there is no plan for a version 10 or even a 9.2. The implication is that users are expected to move to version 9.1. In fact they’ve now announced that previous versions, including our version 8, are only now supported “operationally”. This means that requests for new features will not be acted on. – Or rather the answer is that if you want a new feature, you should ask for a it from a base of being a 9.1 user. That means that we are going to have to bite the bullet and upgrade sooner or later. From a Lincoln point of view, this is going to be quite a large change, as the interface is visually quite different.

You must be logged in to post a comment.